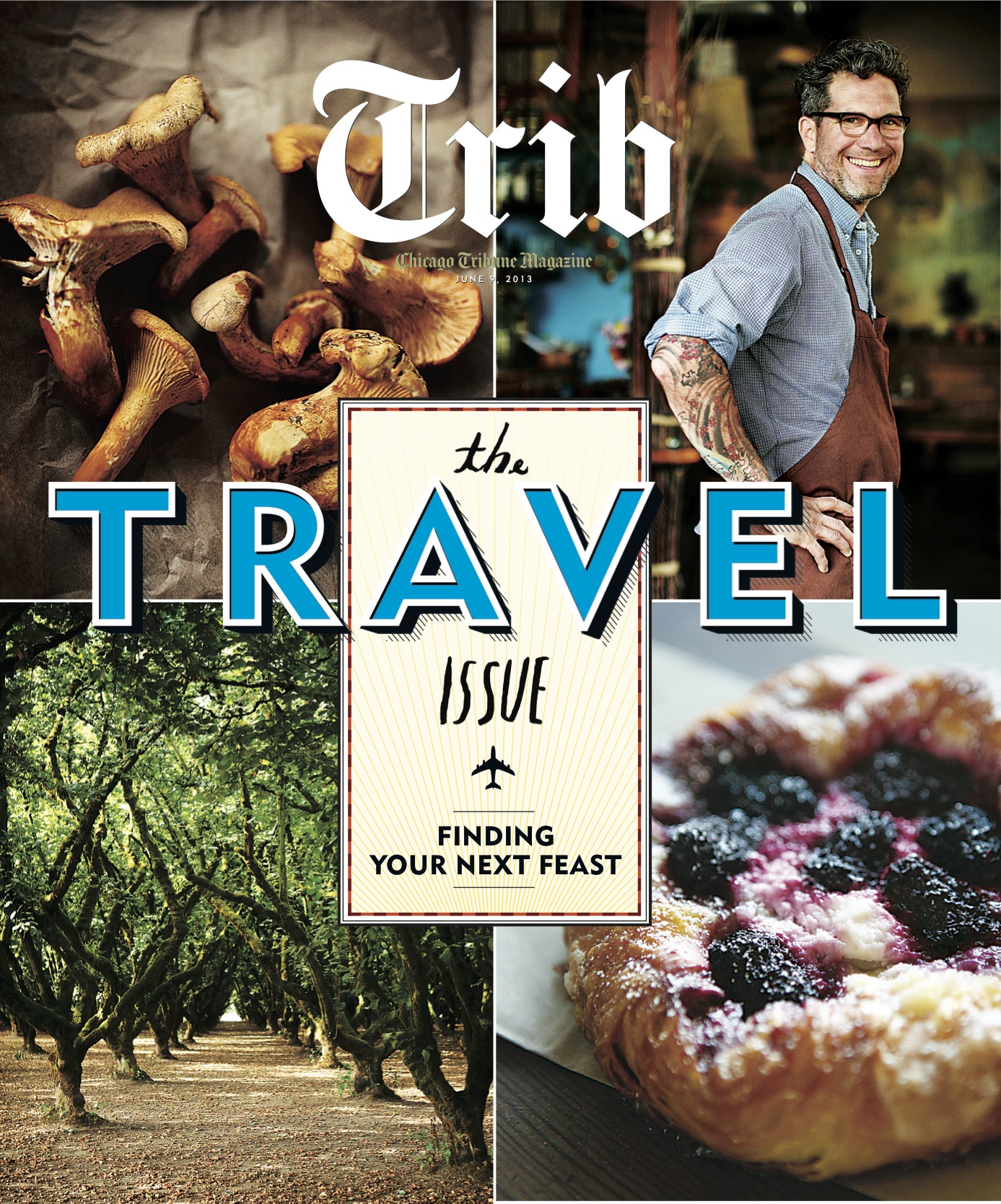

Eating your way through Oregon

Drive a winding road.

Mingle with farmers.

Learn to love getting lost on the trail of farm-to-table goodness

BY CINDY DAMPIER . PHOTOS BY E. JASON WAMBSGANS

On my first morning in Portland, Ore., I headed straight to Broder, a cafe that's a favorite among city chefs and home to a legendary Danish pancake (served in a tiny cast-iron skillet, no less.)

I ordered a coffee. "I'm kinda known for my lattes," countered Joe Conklin, manager at Broder and a food-scene fixture in Portland. He set one in front of me, a perfect drift of fragrant foam skimming across the top. On the first swallow, I decided it was the best latte I'd ever tasted -- rich and satisfying, like the way hot cocoa satisfied when you were a kid. On the third sip I realized why: That wasn't skim milk. It was cream. Make that organic cream, from a farm less than 8 miles from where I was sitting. Conklin shrugged. "That's what makes it best," he said.

That basic understanding -- that great ingredients make the best food you'll ever eat -- is what informs the brilliance of Portland's food scene. And it was what spawned the idea for my trip, a ramble through the city's restaurants and the farms that supply their ingredients.

By dinnertime, I had a handful of recommendations from food types and a seat at the rough-hewn bar at Ned Ludd, where chef Jason French was cooking wild mushrooms foraged from the Oregon woods, using a roaring open hearth.

"The producers are what make Oregon so amazing," he said. "Think of something you're into, and someone here knows someone who's producing it."

It was time to hit the road in search of farms. As searches go, it was almost embarrassingly easy. The historic Columbia River Highway, a winding border between mountains and water, brought me to the Hood River Valley farm country, where the Fruit Loop, a 35-mile drive among farms and farm stands, sprawls along the valley (and along a glossy map you can grab almost anywhere). You can feast, or just feast your eyes; agriculture, as practiced by present-day, food-focused farmers in Oregon, is ridiculously picturesque.

I decided to try both, ending up a little lost, with a Technicolor bunch of dahlias, some pears and too much jam rolling around in the passenger seat. Which is probably why I almost missed the sign for the Jupiter grapes.

If you dreamed up a farm stand, the Cody Orchards farm stand would be it, a low barn beside the road, a little garden with sunflowers and baskets overflowing with just-picked fruit. Proprietor Donna Cody pointed out the grapes touted by the little sign out front before I had time to wonder.

"You have to try them," she said, and so I did, buying a bunch and swiftly throwing a couple into my mouth. The taste left me a little stunned. "These are good!" is all I could manage. Donna looked over. "No. Seriously," I said, still eating.

She explained that they're an old variety of table grape that's being rediscovered, and I bought another bunch, leaving one sparse handful in the bin, out of guilt. The slightly dusty, warm grapes had a taste I couldn't quite place, familiar but not. "It's like a mouthful of wine," Donna said. Or wine crossed with ... Welch's grape juice. If God himself made Welch's.

I ate most of the rest of them sitting in the sunshine on the hood of the rental car. This, I thought to myself, is why I came.

But the grapes were more of a jumping-off point than a destination.

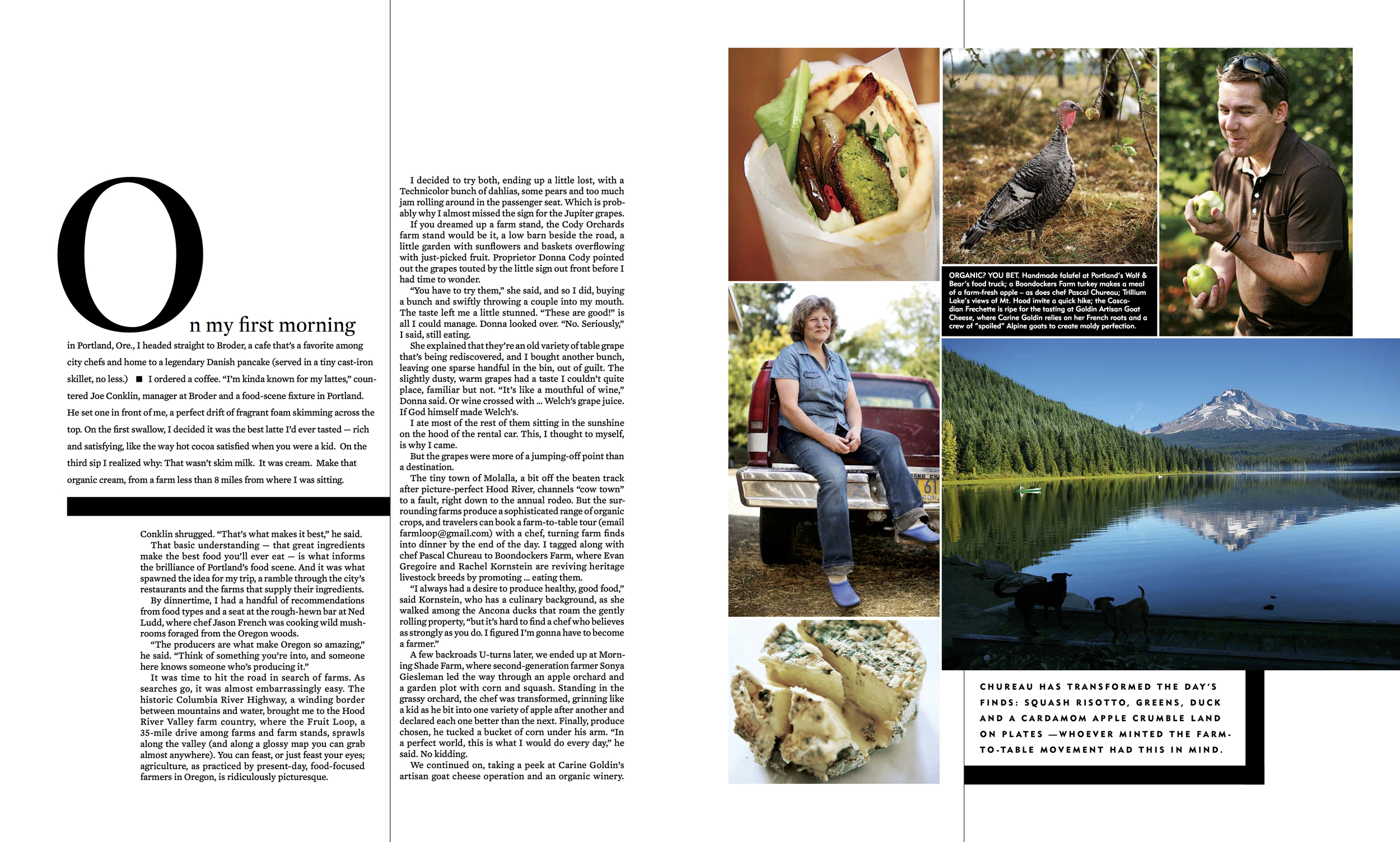

The tiny town of Molalla, a bit off the beaten track after picture-perfect Hood River, channels "cow town" to a fault, right down to the annual rodeo. But the surrounding farms produce a sophisticated range of organic crops, and travelers can book a farm-to-table tour (email farmloop@gmail.com) with a chef, turning farm finds into dinner by the end of the day. I tagged along with chef Pascal Chureau to Boondockers Farm, where Evan Gregoire and Rachel Kornstein are reviving heritage livestock breeds by promoting ... eating them.

"I always had a desire to produce healthy, good food," said Kornstein, who has a culinary background, as she walked among the Ancona ducks that roam the gently rolling property, "but it's hard to find a chef who believes as strongly as you do. I figured I'm gonna have to become a farmer."

A few backroads U-turns later, we ended up at Morning Shade Farm, where second-generation farmer Sonya Giesleman led the way through an apple orchard and a garden plot with corn and squash. Standing in the grassy orchard, the chef was transformed, grinning like a kid as he bit into one variety of apple after another and declared each one better than the next. Finally, produce chosen, he tucked a bucket of corn under his arm. "In a perfect world, this is what I would do every day," he said. No kidding.

We continued on, taking a peek at Carine Goldin's artisan goat cheese operation and an organic winery. A couple hours later, Chureau had transformed the day's finds: squash risotto, greens, duck and a cardamom apple crumble land on plates. Whoever minted the farm-to-table movement must've had this in mind.

A little sunburned, tired and too well-fed, I circled through Portland one last time, stopping in at The Meadow gourmet store -- food seemed like the only appropriate souvenir. I picked up a glass jar of Garibaldi sea salt, promised myself I'd be back and headed out.

Weeks later, back to my daily rounds and to repentant eating habits, I pulled the little salt jar from the cupboard while making dinner. Fragrant, crunchy and earthy, it instantly took me back to my trip.

My 6-year-old, playing sous chef, snuck up behind and stole a pinch from the jar. "Whoa!" he said. "This is good!" I flashed him a grin and a nod.

Quick as a cat, he grabbed another pinch. "Seriously," he said, eyes wide.

Wait 'til I tell him about the grapes.