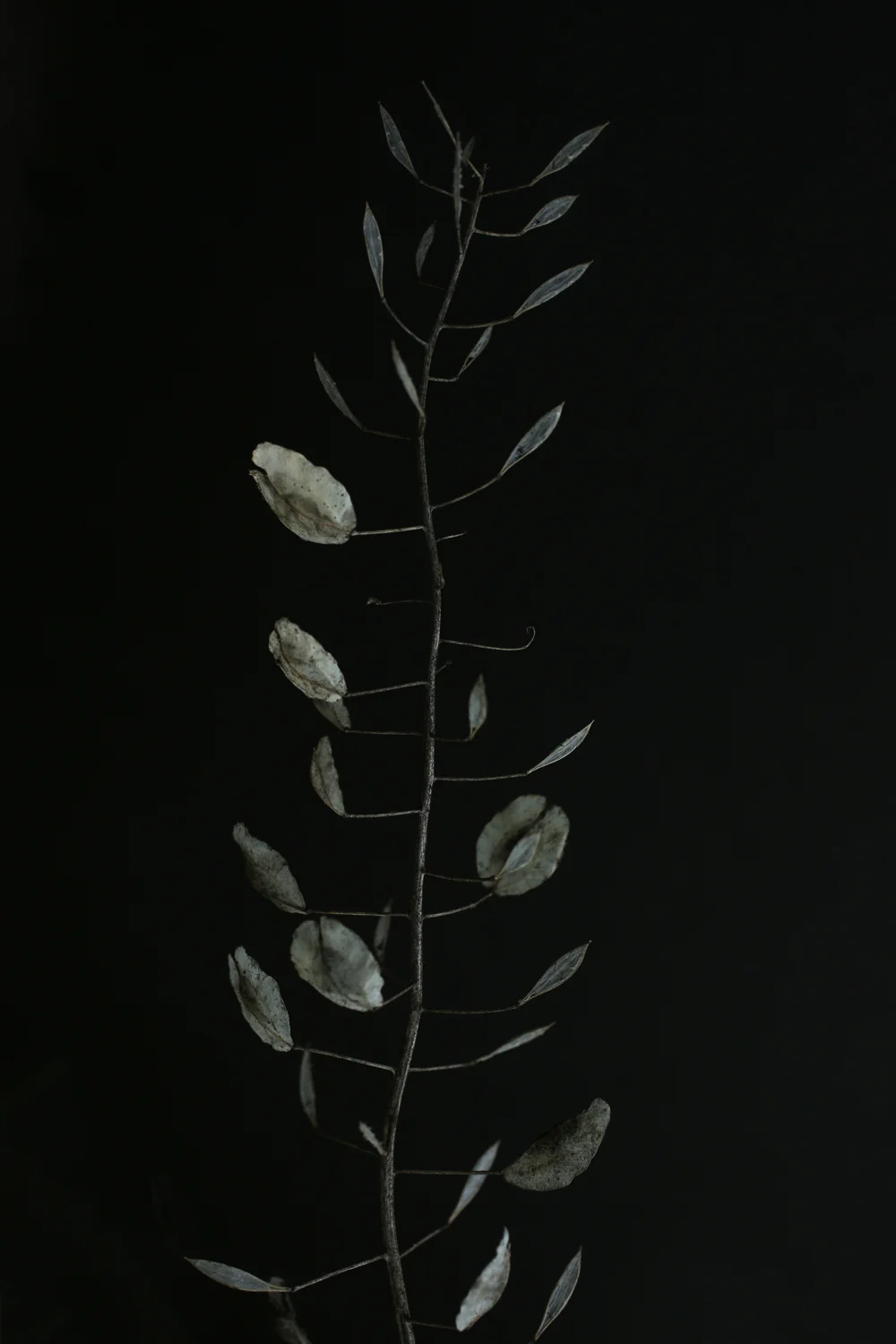

the anti-garden

BY CINDY DAMPIER

PHOTOS BY E. JASON WAMBSGANS

You stand for a minute at the edge of John Mariani’s prairie garden in late summer, pondering your entry into a shifting wall of stalks and stems. The plants, shoulder-height and, bristling with hairs and leaves and the occasional thorn, do not beckon. Still, you plunge in, staggering through as best you can, finding your footing in places you can't quite see, until you are immersed.

The first bug crawls up your forearm, and you flinch, but then more follow, and your twitchier instincts begin to quiet down. You find the will to stand still, and details, otherworldly and beautiful, emerge.

The prairie teems, is teeming, in a way that makes you understand that word as never before. It impresses you as viscerally, almost viciously, alive;, single-mindedly flowering and seeding and crowding and pushing as though you aren't even there. In fact, you realize, you are not. Like water shifting its course, the prairie continues undeterred, unchecked, and essentially uninterested in you. You sense this, and smile.

If you were thinking prairie gardening was all about waving fields of grasses, or miserable-looking weed patches, you'd be wrong.

And if you imagined that John Mariani, landscape architect, master of the North Shore's manicured estate gardens, spends his weekends gazing over a clipped hedge sipping lemonade, you'd be wrong twice.

Most weekends, you can find Mariani in rural Wisconsin, in his prairie garden, looking the way that gardeners do: Eyes cast toward the ground as he walks the paths he has carefully mowed around the property, an ever-present weeding tool in one hand.

"There's one," he mutters, stabbing the business end of his favorite weeder at an interloping weed underfoot. He jabs at it efficiently, gives a small, satisfied grunt, and hoists it up, a small victory.

The property — a broad prairie ringed by hilly wooded savannah — is 60 acres in all: No house. No hedges. No lawns like putting greens. Just Mariani's garden, still a work in progress. And, yes, he's weeding it, all of it, by hand.

"There's more than one man can handle," he says.

Catching the understatement, he laughs.

"I must be crazy doing this. But I really believe eventually I can control it, and I think I can do it myself.”

He’s been trying for 10 years.

When Mariani first saw the property, it was in the process of a different transformation. "The person I bought it from was subdividing it," he says. The gravel drive, aspiring to a planned community aesthetic, was lined with a row of spindly ash trees. But the expanse of rolling plain and the bucolic Wisconsin view that unfolded from the top of the highest hill spoke to Mariani.

He planned a weekend retreat, including a house on the top of that hill to take in the view. But it was the landscape that lit his imagination. “I knew I could do something with this place,” he says. So he sold his home in Lake Forest and opted to rent, rolling the money from the sale of his house into the Wisconsin property.

Drawn to the idea of a naturalistic landscape, he wasn’t quite sure how to start.

“At the time,” he says, “I didn’t really understand savannah or natural prairie or any of that. I did notice there were some plants I’d never seen before. I realized that these were prairie and savannah remnant plants. I got hooked, and it just went from there.”

The work turned out to be more than he bargained for. “You create a prairie by subtraction,” he says. Stripping away invasive and non-native plants, as well as man-made distractions — including 3 miles of barbed wire and steel posts, by his count — Mariani uncovered hoped-for signs of the prairie. Long-dormant under a layer of invasive buckthorn and honeysuckle that he cleared along an old fenceline, bottlebrush and big bluestem grasses emerged and started growing again. “It’s like finding buried treasure,” Mariani says. “The first time I saw big bluestem growing wild was on my property. That’s the tallgrass grass. I knew we had something here.”

Controlled burning and herbicides — necessary to help tamp down tough invasive plants — made more room for natives to return, and created fertile ground for seeding. Mariani hand-picked native plants for the seed mixture, and, slowly, the delicately layered world of the prairie returned.

Wildlife traffic increased, too. Mariani spotted a rough-legged hawk, wintering from its home on the tundra, along with deer, coyotes, and endless butterflies. “I tried to get as much diversity as I could here,” Mariani says, “and with diversity you get more creatures. I’ve found several kinds of snakes, frogs ... Whippoorwills, which I hadn’t heard since I was a child, come every evening.”

As the prairie’s density increased, Mariani started to see the design in his wild garden. “People think of prairies as weed patches or no order,” he says. “But some vignettes are perfect compositions if you focus.” What he saw was subtle, yet dramatic: Late summer’s last light might fall on a stand of asters in rich shades of purple. Morning dew silvered the lines of nodding grasses in early autumn, and a spring snow revealed a lone tree, a giant punctuating the curve of a hill. At work in all seasons, Mariani’s eyes tracked the contours of the land and saw where to thread a few curving paths that would disappear, inviting you to follow. “Every move I make with that mower is mapped out first,” he says. “I’m thinking of all that stuff and at the same time trying to tread as lightly as I possibly can on the land.”

It’s an interesting goal, coming from a man whose stock in trade has been the hyper-controlled landscape of high-end suburbia. “My specialty is formal, Italian gardens,” he says, “and I love them. But what I do personally has a different feel. It’s an anti-garden.”

In fact, as his prairie has taken root, the cause of native plants has become firmly entrenched in Mariani’s evolving design philosophy. He routinely convinces clients to tuck pocket-sized prairies into the outer reaches of their properties, or even to cultivate larger swaths complete with paths, hidden gazebos and entertaining spaces. Next up: Finding a way to create more traditional landscapes that are native-plant friendly. “The savannah is one of the rarest ecosystems around,” he says. “People can't relate to grasses, they think it’s weeds. So the challenge is to come up with a way to design with native plants that's more acceptable to the average person.

“It's really important work, because we're losing our natural lands, native habitat, native plants. Growing up, I saw prairies and I saw animals that slowly disappeared from the place where I lived. I'm trying to bring that back.”

Which is why, if you pay a visit to Mariani’s prairie in winter, on a day when the cold eases but the air is still crisp and dry and the hawk is teetering high above the oaks, you’ll find him hard at work, still clearing and burning brush with a cheerful, hard-headed fervor. “I find myself with a smile on my face while I'm working my ass off,” he says. “I know every time I pull that buckthorn and clear the junk out that I'm freeing the land.”

As for that dream house? Work is beginning, just barely, but Mariani isn’t rushing it. “Nature,” he says with a shrug, “has always been more important to me than the house.”

Eating your way through Oregon

Drive a winding road.

Mingle with farmers.

Learn to love getting lost on the trail of farm-to-table goodness

BY CINDY DAMPIER . PHOTOS BY E. JASON WAMBSGANS

On my first morning in Portland, Ore., I headed straight to Broder, a cafe that's a favorite among city chefs and home to a legendary Danish pancake (served in a tiny cast-iron skillet, no less.)

I ordered a coffee. "I'm kinda known for my lattes," countered Joe Conklin, manager at Broder and a food-scene fixture in Portland. He set one in front of me, a perfect drift of fragrant foam skimming across the top. On the first swallow, I decided it was the best latte I'd ever tasted -- rich and satisfying, like the way hot cocoa satisfied when you were a kid. On the third sip I realized why: That wasn't skim milk. It was cream. Make that organic cream, from a farm less than 8 miles from where I was sitting. Conklin shrugged. "That's what makes it best," he said.

That basic understanding -- that great ingredients make the best food you'll ever eat -- is what informs the brilliance of Portland's food scene. And it was what spawned the idea for my trip, a ramble through the city's restaurants and the farms that supply their ingredients.

By dinnertime, I had a handful of recommendations from food types and a seat at the rough-hewn bar at Ned Ludd, where chef Jason French was cooking wild mushrooms foraged from the Oregon woods, using a roaring open hearth.

"The producers are what make Oregon so amazing," he said. "Think of something you're into, and someone here knows someone who's producing it."

It was time to hit the road in search of farms. As searches go, it was almost embarrassingly easy. The historic Columbia River Highway, a winding border between mountains and water, brought me to the Hood River Valley farm country, where the Fruit Loop, a 35-mile drive among farms and farm stands, sprawls along the valley (and along a glossy map you can grab almost anywhere). You can feast, or just feast your eyes; agriculture, as practiced by present-day, food-focused farmers in Oregon, is ridiculously picturesque.

I decided to try both, ending up a little lost, with a Technicolor bunch of dahlias, some pears and too much jam rolling around in the passenger seat. Which is probably why I almost missed the sign for the Jupiter grapes.

If you dreamed up a farm stand, the Cody Orchards farm stand would be it, a low barn beside the road, a little garden with sunflowers and baskets overflowing with just-picked fruit. Proprietor Donna Cody pointed out the grapes touted by the little sign out front before I had time to wonder.

"You have to try them," she said, and so I did, buying a bunch and swiftly throwing a couple into my mouth. The taste left me a little stunned. "These are good!" is all I could manage. Donna looked over. "No. Seriously," I said, still eating.

She explained that they're an old variety of table grape that's being rediscovered, and I bought another bunch, leaving one sparse handful in the bin, out of guilt. The slightly dusty, warm grapes had a taste I couldn't quite place, familiar but not. "It's like a mouthful of wine," Donna said. Or wine crossed with ... Welch's grape juice. If God himself made Welch's.

I ate most of the rest of them sitting in the sunshine on the hood of the rental car. This, I thought to myself, is why I came.

But the grapes were more of a jumping-off point than a destination.

The tiny town of Molalla, a bit off the beaten track after picture-perfect Hood River, channels "cow town" to a fault, right down to the annual rodeo. But the surrounding farms produce a sophisticated range of organic crops, and travelers can book a farm-to-table tour (email farmloop@gmail.com) with a chef, turning farm finds into dinner by the end of the day. I tagged along with chef Pascal Chureau to Boondockers Farm, where Evan Gregoire and Rachel Kornstein are reviving heritage livestock breeds by promoting ... eating them.

"I always had a desire to produce healthy, good food," said Kornstein, who has a culinary background, as she walked among the Ancona ducks that roam the gently rolling property, "but it's hard to find a chef who believes as strongly as you do. I figured I'm gonna have to become a farmer."

A few backroads U-turns later, we ended up at Morning Shade Farm, where second-generation farmer Sonya Giesleman led the way through an apple orchard and a garden plot with corn and squash. Standing in the grassy orchard, the chef was transformed, grinning like a kid as he bit into one variety of apple after another and declared each one better than the next. Finally, produce chosen, he tucked a bucket of corn under his arm. "In a perfect world, this is what I would do every day," he said. No kidding.

We continued on, taking a peek at Carine Goldin's artisan goat cheese operation and an organic winery. A couple hours later, Chureau had transformed the day's finds: squash risotto, greens, duck and a cardamom apple crumble land on plates. Whoever minted the farm-to-table movement must've had this in mind.

A little sunburned, tired and too well-fed, I circled through Portland one last time, stopping in at The Meadow gourmet store -- food seemed like the only appropriate souvenir. I picked up a glass jar of Garibaldi sea salt, promised myself I'd be back and headed out.

Weeks later, back to my daily rounds and to repentant eating habits, I pulled the little salt jar from the cupboard while making dinner. Fragrant, crunchy and earthy, it instantly took me back to my trip.

My 6-year-old, playing sous chef, snuck up behind and stole a pinch from the jar. "Whoa!" he said. "This is good!" I flashed him a grin and a nod.

Quick as a cat, he grabbed another pinch. "Seriously," he said, eyes wide.

Wait 'til I tell him about the grapes.

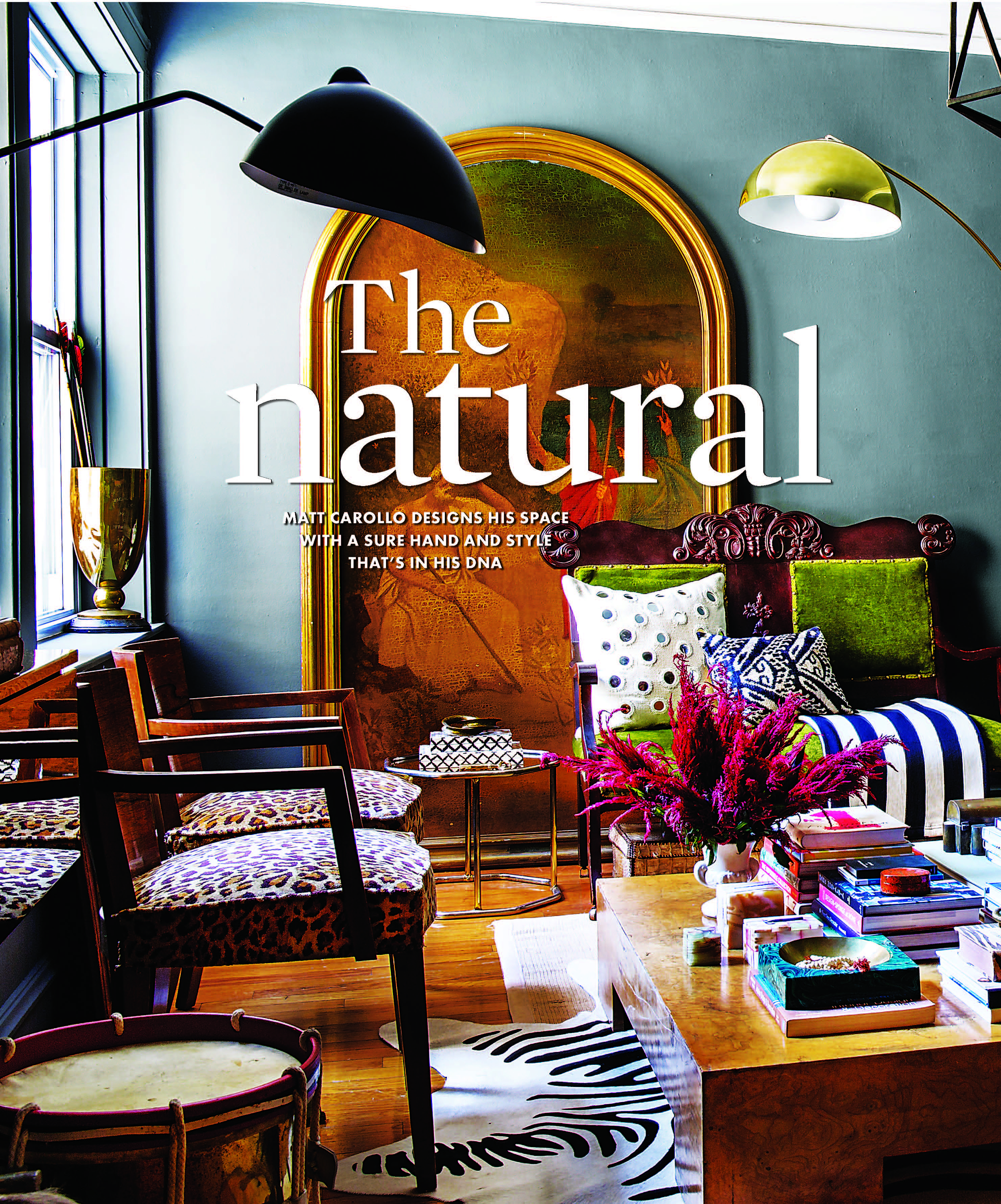

the natural

Matt Carollo designs his space with a sure hand — and style that's in his DNA

BY CINDY DAMPIER . PHOTOS BY BILL HOGAN

The mailbox is the first sign that things are different in Apartment One.

In a vintage building on Chicago’s north side, residents’ names are hand-scrawled on pieces of tape between the row of little metal boxes and an angry reminder from the postal carrier. (“No name no mail!”) All but one. “Carollo,” reads a tidy label neatly centered on the first box in the row — a small clue that the owner of that mailbox isn’t fooling around. Details matter to Matt Carollo.

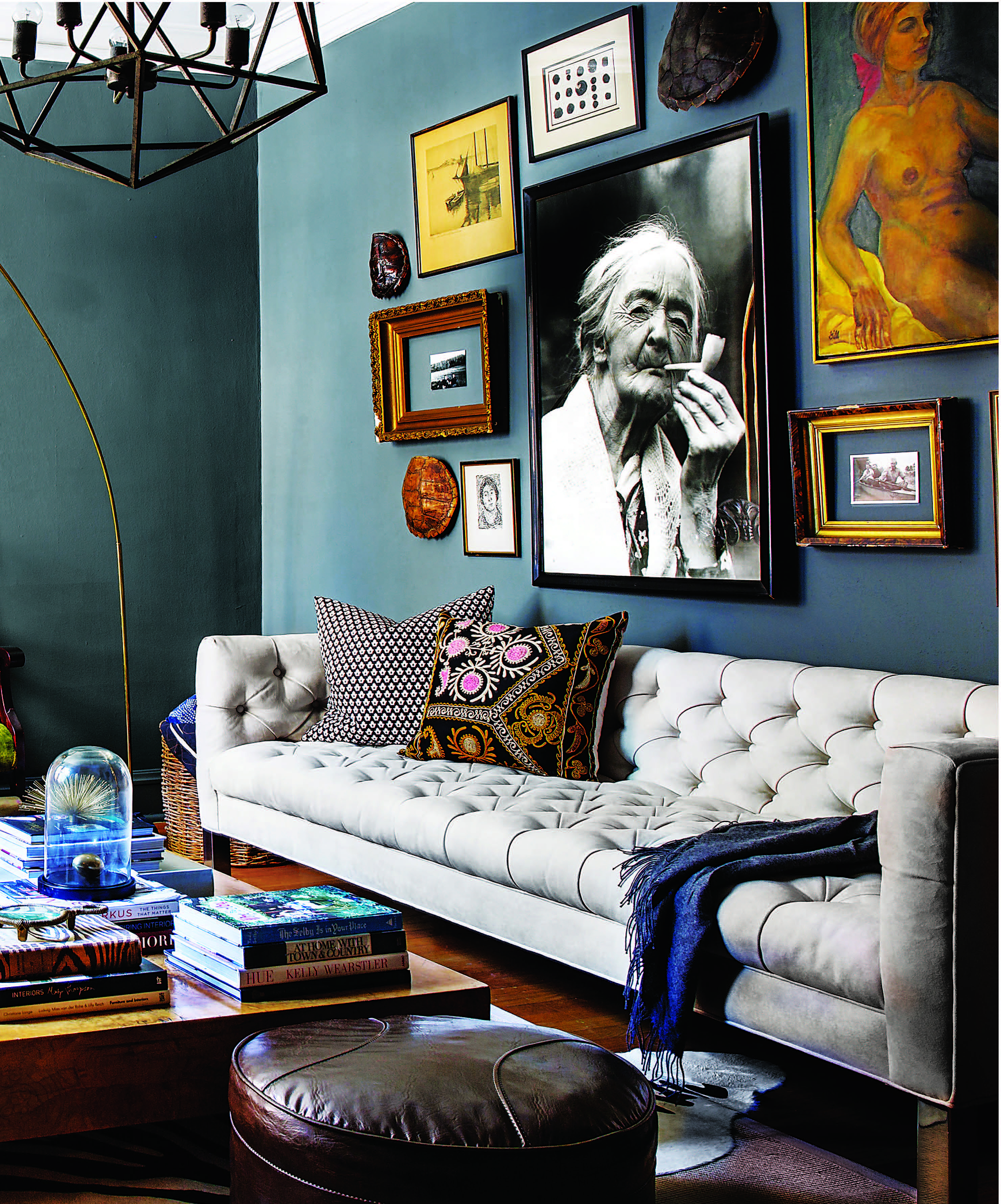

“I think I knew what I was going to do from the time I was 12,” he says, and when you step into his place, you get it. The postage-stamp-size foyer has a chandelier, (‘It was hanging in my parents’ basement,” Carollo says, “and my mom was thinking of using it but I said, no, wait, I’m going to need it.”) two vintage portraits of real-deal ancestors in heavy gilt frames, and black walls with matching glossy black trim. Around the edges of the tiny square of wood floor is another defining detail: a trim black stripe. “It’s the tape that they use to mark basketball courts,” says Carollo, who never fails to cop to his DIY side. “It stays in place really well, except for one little part where I was moving the sofa.”

The living room, you see, used to be stationed over here — where the dining room is now.

That’s how it goes Chez Carollo, the home of Jayson Home’s assistant buyer, who seems to not only have found the job that suits him perfectly, but an innate style at home.

It’s a style informed by a lifetime of collecting. Growing up in rural Michigan, he says, “there wasn’t much to do in our town except shop.” And so he found himself tagging along to antiques stores and auctions with his mother, developing an eye for a good light fixture or a well-priced credenza at a precocious age. In high school, he held a job in an antiques store, further cementing his love of (and access to) all things vintage. Which partly explains why, the second he took possession of his present rental, Carollo was able to replace all the light fixtures with vintage lights which range from delicate dangling crystals to geometric midcentury brass-and-glass. He also tackled a kitchen with cupboards painted with a single slipshod coat of white paint, over the previous tenant’s bright red. “I wish I liked red,” he says, “but I just can’t do it.” He remedied the sickly pink that remained with a signature paint color, Farrow & Ball’s Down Pipe, which he also used in the living room.

If DIY is one pillar of Carollo’s style, an unabashed love of more — small space be damned — is another. “People talk about the one in, one out rule,” he says. “Here it’s just one in.” His rooms are intensely layered and personal. “If I can’t stop thinking about something, I know it has to come home with me. And if I really love something, I’ll find a way to use it.” In the living room, a settee that belonged to his great-grandmother, and was reupholstered by her in jewel-green mohair, presides over a Milo Baughman-style burled wood coffee table. “I had seen it in an antiques place,” says Carollo, “and decided I had to get it. But when I went back, it was gone. I was walking around the store, kind of depressed, and a woman asked if she could help me. I asked about it, and she said, ‘Oh yeah, it was so big that we finally had to move it out of the way somewhere.’” He got it for a song, “and then I knew I had to look for an apartment that would fit that table.” And it does — stacked high with coffee table books and chosen objects, or cleared off for board games or Thai take-out with friends, it grounds the space in both function and unswerving style. Just as Carollo knew it would.

Second nature

Matt Carollo on how to make your space a showcase for your style

Avoid distractions. “Trends come and go quickly,” says Carollo. “I might buy something that’s on trend, but if I buy it, it’s because I really love it, so I know it will stay with me.” Instead of trying for a look defined by someone else, buy things you love and your own look will begin to emerge.

Start early. “I was buying things I saw and storing them at my parents’ house even before I had a place to put them,” he says. Even in a first apartment, a vintage piece or eye-catching find brings more personality to the picture than a room full of brand-new things.

Mix well. “I love so many styles and periods,” Carollo says, “and they really can all look good together. I love the ornate carved edge of a table against the modern lines of old wire chairs.” A lively mix allows you to sneak in big box purchases, too — like Carollo’s IKEA lacquer and Serge Mouille-knockoff lamps that gain elegance from surrounding pieces.

Get dirty. DIY, not just design, is in Carollo’s DNA — his great grandmother was known to tackle her own upholstery work. Among his current projects: an upholstered bed, restored brass hardware on doors, and a kitchen countertop that he sanded and coated with patching cement to get the (absolutely credible) look of a cement countertop. “I’m not afraid of a little work to change things and make them how I want them to be,” he says.

Go bold. Confidence is stylish, so don’t stop short of a big gesture. “People always try to talk me out of dark colors,” says Carollo, “but I love them.” His dark-painted walls create an elegant, dramatic backdrop that works well with his things.