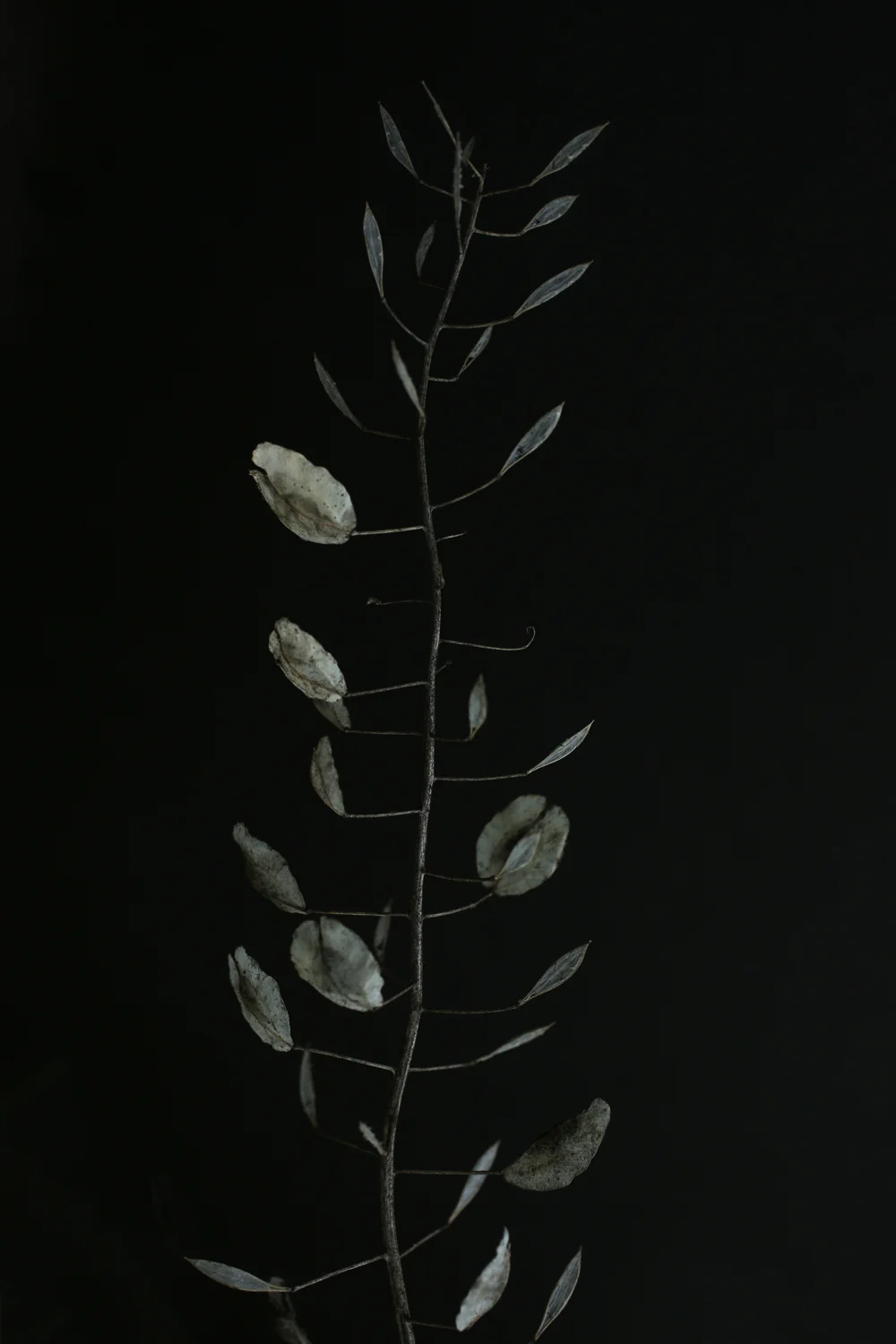

the anti-garden

BY CINDY DAMPIER

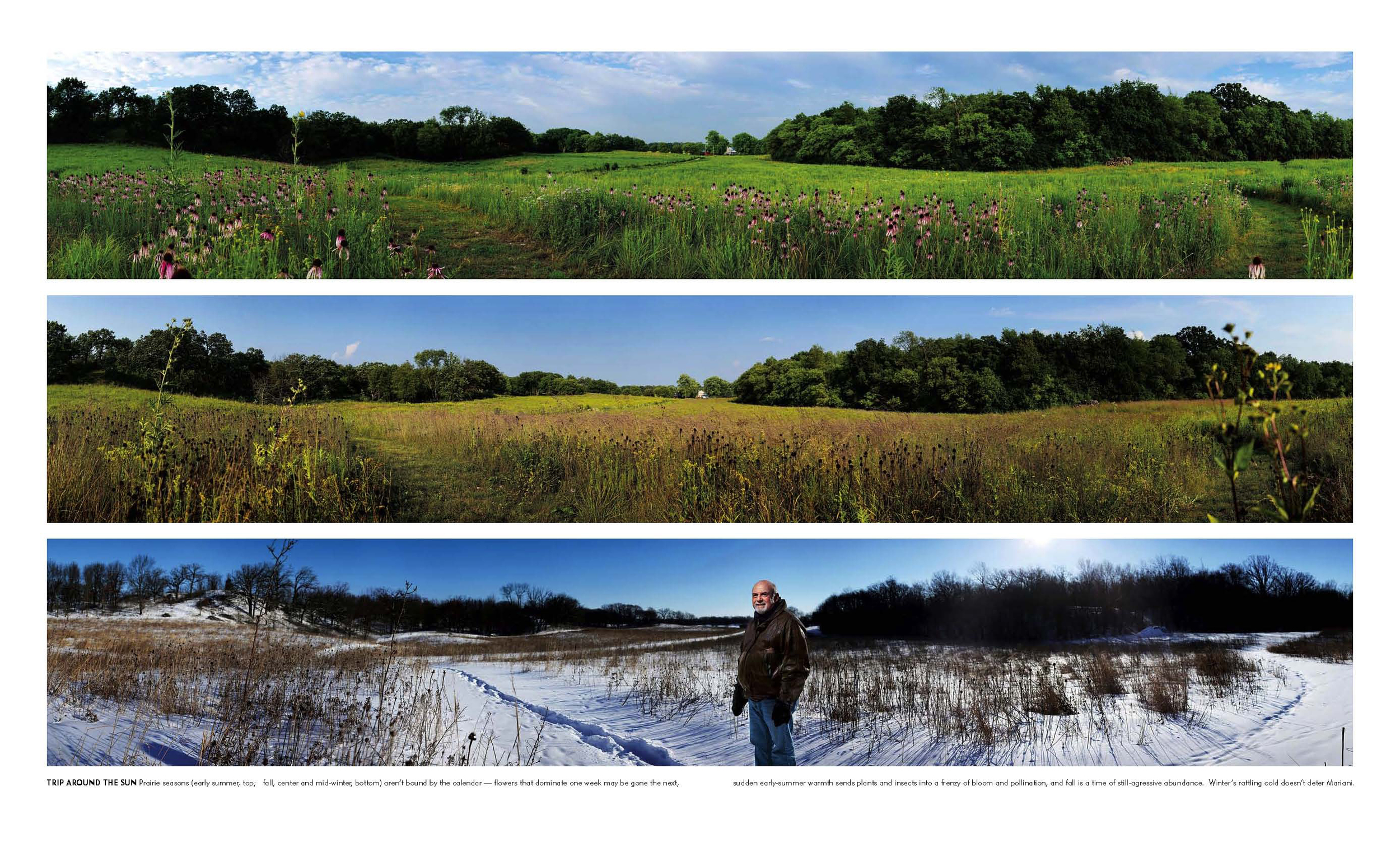

PHOTOS BY E. JASON WAMBSGANS

You stand for a minute at the edge of John Mariani’s prairie garden in late summer, pondering your entry into a shifting wall of stalks and stems. The plants, shoulder-height and, bristling with hairs and leaves and the occasional thorn, do not beckon. Still, you plunge in, staggering through as best you can, finding your footing in places you can't quite see, until you are immersed.

The first bug crawls up your forearm, and you flinch, but then more follow, and your twitchier instincts begin to quiet down. You find the will to stand still, and details, otherworldly and beautiful, emerge.

The prairie teems, is teeming, in a way that makes you understand that word as never before. It impresses you as viscerally, almost viciously, alive;, single-mindedly flowering and seeding and crowding and pushing as though you aren't even there. In fact, you realize, you are not. Like water shifting its course, the prairie continues undeterred, unchecked, and essentially uninterested in you. You sense this, and smile.

If you were thinking prairie gardening was all about waving fields of grasses, or miserable-looking weed patches, you'd be wrong.

And if you imagined that John Mariani, landscape architect, master of the North Shore's manicured estate gardens, spends his weekends gazing over a clipped hedge sipping lemonade, you'd be wrong twice.

Most weekends, you can find Mariani in rural Wisconsin, in his prairie garden, looking the way that gardeners do: Eyes cast toward the ground as he walks the paths he has carefully mowed around the property, an ever-present weeding tool in one hand.

"There's one," he mutters, stabbing the business end of his favorite weeder at an interloping weed underfoot. He jabs at it efficiently, gives a small, satisfied grunt, and hoists it up, a small victory.

The property — a broad prairie ringed by hilly wooded savannah — is 60 acres in all: No house. No hedges. No lawns like putting greens. Just Mariani's garden, still a work in progress. And, yes, he's weeding it, all of it, by hand.

"There's more than one man can handle," he says.

Catching the understatement, he laughs.

"I must be crazy doing this. But I really believe eventually I can control it, and I think I can do it myself.”

He’s been trying for 10 years.

When Mariani first saw the property, it was in the process of a different transformation. "The person I bought it from was subdividing it," he says. The gravel drive, aspiring to a planned community aesthetic, was lined with a row of spindly ash trees. But the expanse of rolling plain and the bucolic Wisconsin view that unfolded from the top of the highest hill spoke to Mariani.

He planned a weekend retreat, including a house on the top of that hill to take in the view. But it was the landscape that lit his imagination. “I knew I could do something with this place,” he says. So he sold his home in Lake Forest and opted to rent, rolling the money from the sale of his house into the Wisconsin property.

Drawn to the idea of a naturalistic landscape, he wasn’t quite sure how to start.

“At the time,” he says, “I didn’t really understand savannah or natural prairie or any of that. I did notice there were some plants I’d never seen before. I realized that these were prairie and savannah remnant plants. I got hooked, and it just went from there.”

The work turned out to be more than he bargained for. “You create a prairie by subtraction,” he says. Stripping away invasive and non-native plants, as well as man-made distractions — including 3 miles of barbed wire and steel posts, by his count — Mariani uncovered hoped-for signs of the prairie. Long-dormant under a layer of invasive buckthorn and honeysuckle that he cleared along an old fenceline, bottlebrush and big bluestem grasses emerged and started growing again. “It’s like finding buried treasure,” Mariani says. “The first time I saw big bluestem growing wild was on my property. That’s the tallgrass grass. I knew we had something here.”

Controlled burning and herbicides — necessary to help tamp down tough invasive plants — made more room for natives to return, and created fertile ground for seeding. Mariani hand-picked native plants for the seed mixture, and, slowly, the delicately layered world of the prairie returned.

Wildlife traffic increased, too. Mariani spotted a rough-legged hawk, wintering from its home on the tundra, along with deer, coyotes, and endless butterflies. “I tried to get as much diversity as I could here,” Mariani says, “and with diversity you get more creatures. I’ve found several kinds of snakes, frogs ... Whippoorwills, which I hadn’t heard since I was a child, come every evening.”

As the prairie’s density increased, Mariani started to see the design in his wild garden. “People think of prairies as weed patches or no order,” he says. “But some vignettes are perfect compositions if you focus.” What he saw was subtle, yet dramatic: Late summer’s last light might fall on a stand of asters in rich shades of purple. Morning dew silvered the lines of nodding grasses in early autumn, and a spring snow revealed a lone tree, a giant punctuating the curve of a hill. At work in all seasons, Mariani’s eyes tracked the contours of the land and saw where to thread a few curving paths that would disappear, inviting you to follow. “Every move I make with that mower is mapped out first,” he says. “I’m thinking of all that stuff and at the same time trying to tread as lightly as I possibly can on the land.”

It’s an interesting goal, coming from a man whose stock in trade has been the hyper-controlled landscape of high-end suburbia. “My specialty is formal, Italian gardens,” he says, “and I love them. But what I do personally has a different feel. It’s an anti-garden.”

In fact, as his prairie has taken root, the cause of native plants has become firmly entrenched in Mariani’s evolving design philosophy. He routinely convinces clients to tuck pocket-sized prairies into the outer reaches of their properties, or even to cultivate larger swaths complete with paths, hidden gazebos and entertaining spaces. Next up: Finding a way to create more traditional landscapes that are native-plant friendly. “The savannah is one of the rarest ecosystems around,” he says. “People can't relate to grasses, they think it’s weeds. So the challenge is to come up with a way to design with native plants that's more acceptable to the average person.

“It's really important work, because we're losing our natural lands, native habitat, native plants. Growing up, I saw prairies and I saw animals that slowly disappeared from the place where I lived. I'm trying to bring that back.”

Which is why, if you pay a visit to Mariani’s prairie in winter, on a day when the cold eases but the air is still crisp and dry and the hawk is teetering high above the oaks, you’ll find him hard at work, still clearing and burning brush with a cheerful, hard-headed fervor. “I find myself with a smile on my face while I'm working my ass off,” he says. “I know every time I pull that buckthorn and clear the junk out that I'm freeing the land.”

As for that dream house? Work is beginning, just barely, but Mariani isn’t rushing it. “Nature,” he says with a shrug, “has always been more important to me than the house.”